A Vision of Love Revealed in Sleep

14 November 2025 - 17 January 2026

SID MOTION GALLERY

exhibition text by Tom Denman

“Silveria Martin’s way of applying transparent paints to a base of loosely squeegeed diluted gesso, producing random shadowy traces and layered streaks, affords a sense of looking back and forth. Of the past rebounding in the present, disappearing and reappearing in non-linear, ruptured, furtive ways. The eye flits between looking at and looking through, like in a mirror or through a window and your focus shifts to a smear on the surface and what lies beyond it momentarily vanishes.”

Tom Denman, 2025

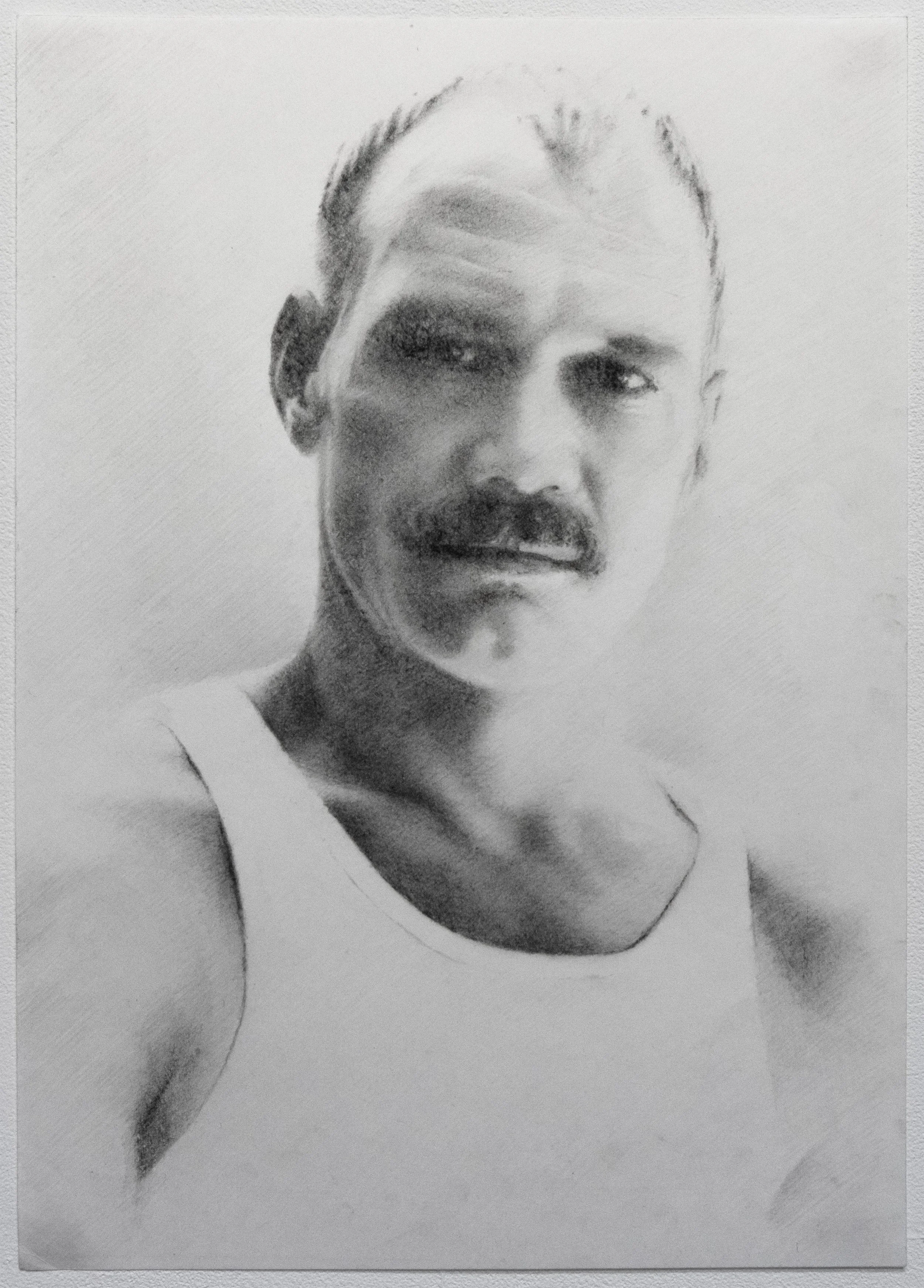

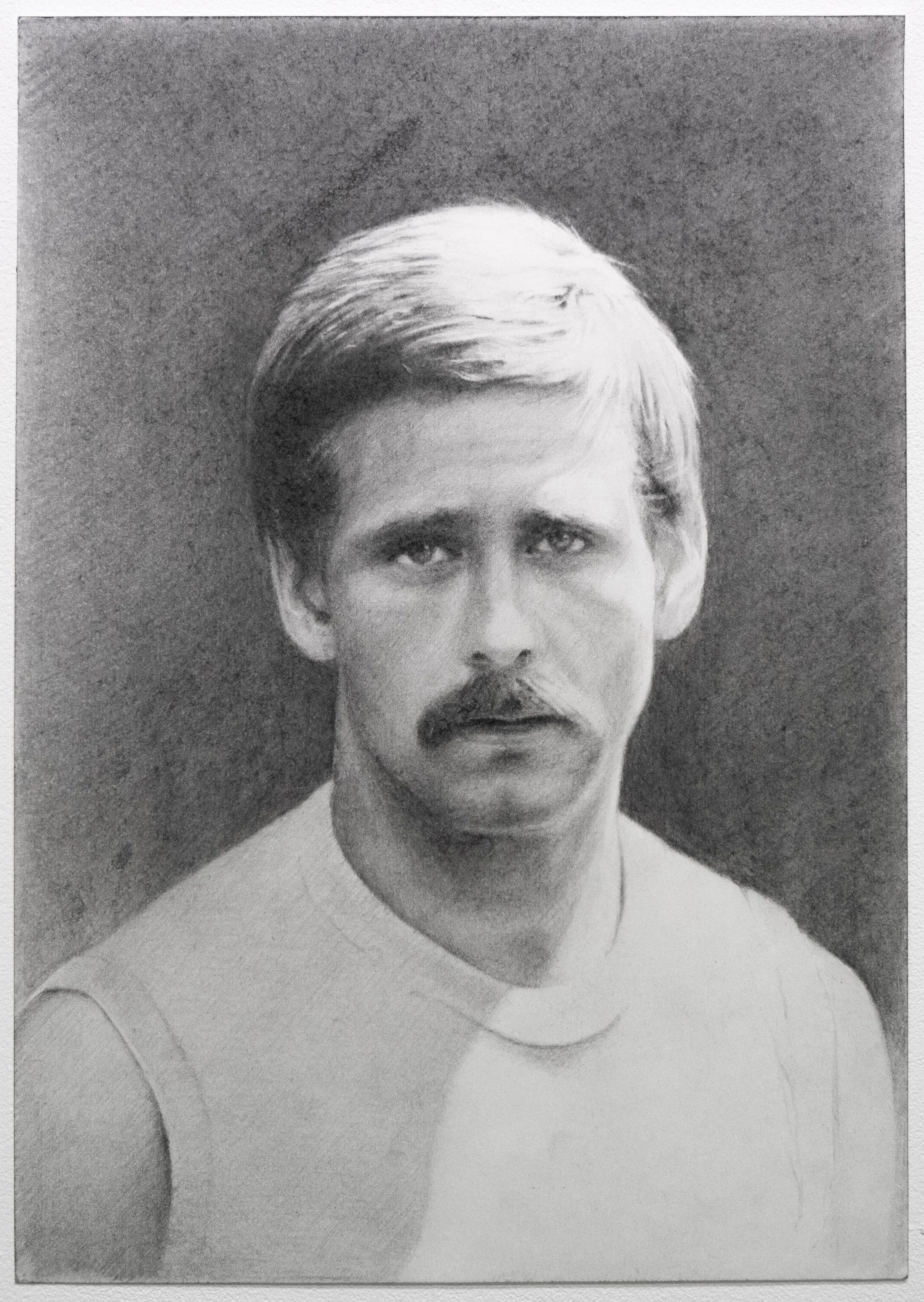

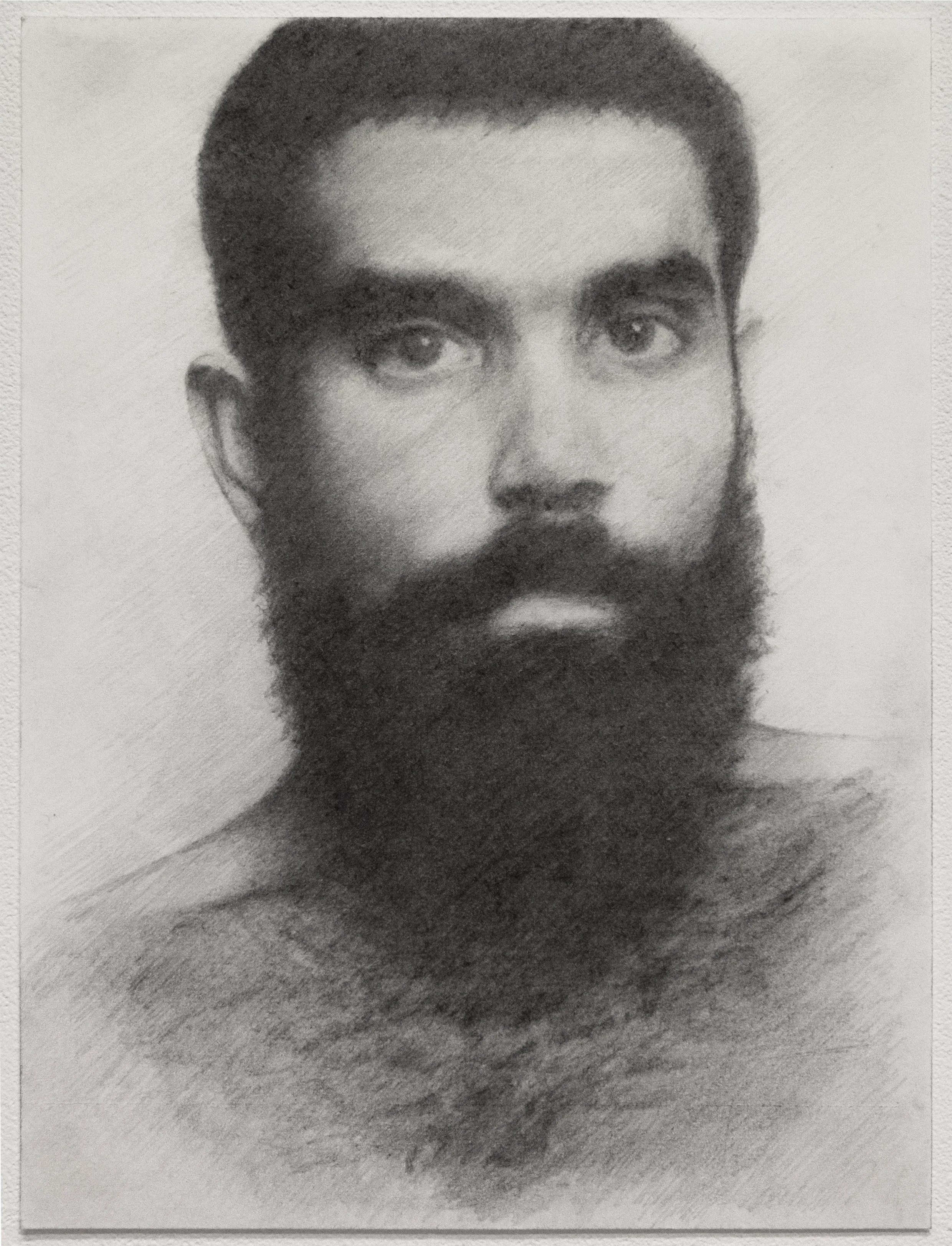

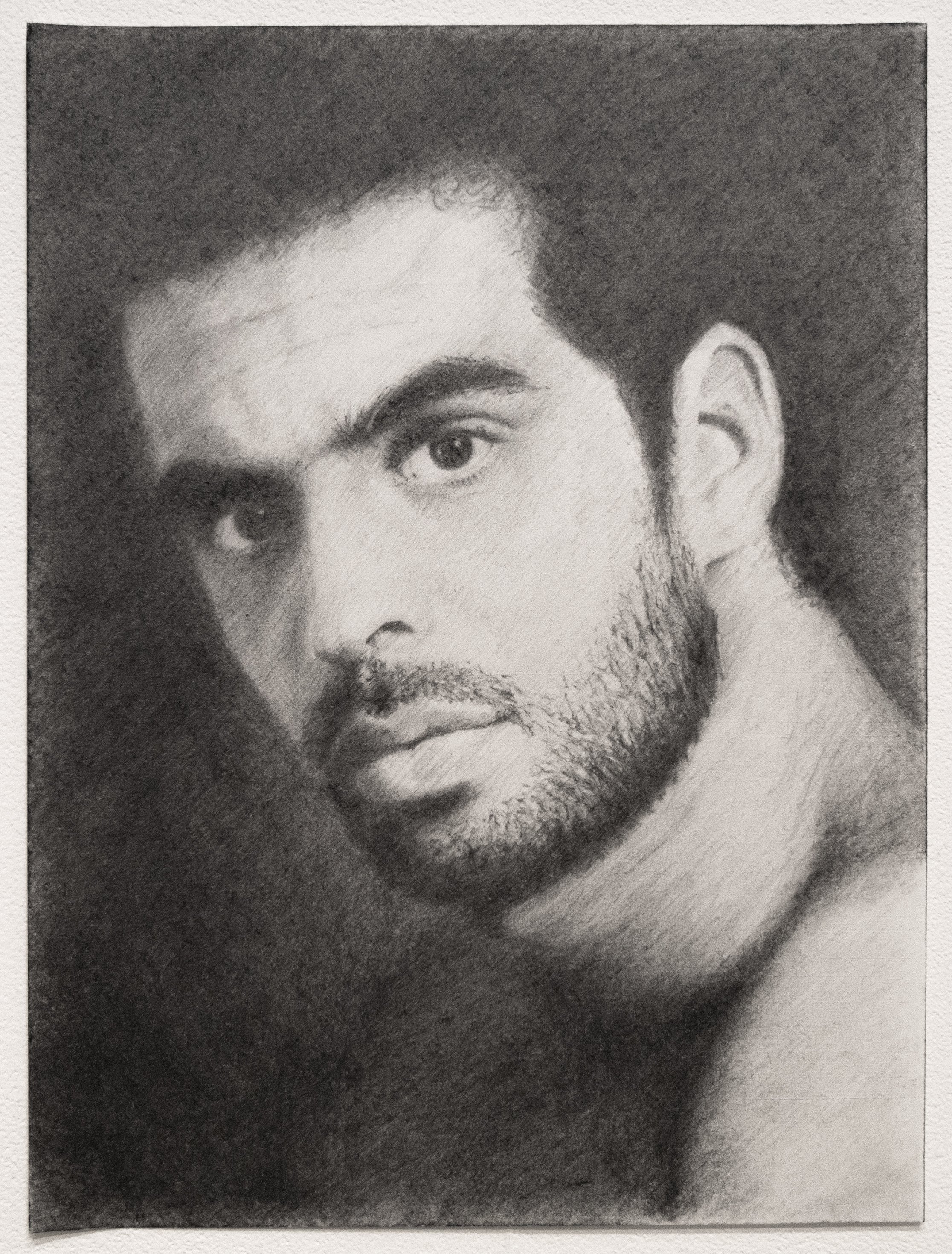

A Vision of Love Revealed in Sleep is an exhibition of drawings and paintings by Graham Silveria Martin exploring themes of connection, desire and collective memory, whilst tracing sensibilities across time. Typically working with found imagery, Silveria Martin’s recent work draws predominantly from ‘Blueboy’, a men’s magazine published from 1974–2007, taking its name from Thomas Gainsborough’s painting, c. 1770.

The Greco-Roman references in these magazines prompted Silveria Martin to explore the V&A’s sculpture collection, responding to marble groups that he felt held a certain queer erotic charge. During these visits he discovered work by Lord Frederic Leighton. Shared sensibilities and coded signifiers in Leighton’s work led him to explore other artists of the period celebrating aestheticist ideals.

The work in the exhibition draws from a variety of sources dating from the 16th century to the present day, from gay magazines published in the late 1970s, Victorian and Modernist influences in the work of Leighton, Simeon Solomon and Duncan Grant, to the classical sculpture of Giambologna and Canova. The exhibition also includes two erotic drawings by Duncan Grant from the 1950s.

The exhibition is titled after a poem by the 19th-century artist Simeon Solomon. Solomon’s artistic career was cut short due to the public scandal and disgrace he faced as a result of his same-sex relationships.

Cruising Time

by Tom Denman

The more I think about it, the more apt it seems to imagine the museum as a cruising ground. Not necessarily as somewhere you might seek casual sex – although it might be that, too – but as a place, or palace, full of phantasmically whispered suggestive codes. I am lured to this conclusion after spending considerable time looking at the paintings and drawings of Graham Silveria Martin. In a photorealistic manner, and building up the surfaces of his canvases with translucent, washy stains and strata, the Scottish artist has committed much of his recent practice to reproducing erotically charged depictions of men seen in Renaissance and neoclassical art as well as their aesthetic rebirth in the more explicitly sexual context of the gay men’s magazine.

Aside from his considered method of layering paint, crucial to Silveria Martin’s approach – we might call it his starting point – especially in his paintings of marble sculptures, is the crop. It suggests the furtive glance: the moment of identification and recognition that animates an encounter, jolting between ambiguity and certainty (does this mean sex? it definitely means sex…), with the artefact on display. Such an artefact may as well be displaying itself, or a secret that anyone with their wits about them, or anyone in on it, knows.

Thus the queer gaze disorients the museum from the limits of evidence, or the rigidity of formal academic study. There is nothing to prove that the Italian sculptor Giambologna intended a homoerotic response to his Samson Slaying the Philistine (c. 1562) in the Victoria & Albert Museum, yet his spiralling composition asks us to look at it from three hundred and sixty degrees. Circling the larger-than-life marble wonder, Silveria Martin homes in on a segment, approximating a passerby’s field of vision (Samson, 2025). We see Samson’s buttocks and they fit the Herculean ideal, as ‘perfect’ today as they were in the 16th century, with the Philistine’s arm helplessly hooked round his thigh. Crucial is Samson’s downward-jutting forearm, only part of which is visible – enough for us to picture it forcing the Philistine’s head against whatever throbs on the other side of his vanquisher’s arse.

Head along the sculpture corridor back the way you came, up the stairwell till you reach the second floor, then go straight ahead for a bit and you’ll find on your left another fantasy. In muted, rusty browns and creams, seated in the foreground of this large drawing are women sewing, while behind them four men are cladding themselves for battle. This is the segment of Frederic Leighton’s The Arts of Industry as Applied to War (1870–72), the cartoon for a fresco around the corner, that Silveria Martin has cropped and expanded in The Arts of Industry (after Leighton) (2025). The copy mimics the doubletake – for what are these men really doing? The chap currently being armoured could be having erotic dream, his eyes closed with ecstatic abandon; another with his back to us tugs at the heal of his shoe, thereby drawing the eye to his pert bum – a code, perhaps? He knows you are looking at him.

Silveria Martin is not necessarily trying to say anything about Leighton himself – the Victorian artist’s sexuality is an ongoing topic of debate – as much as inviting us to participate in a queer phenomenology, something he has described, to me, as ‘cruising the museum’. Our reaction to these images engenders narratives, actual and speculative, past, present and possible, born of censorial absences in the archive – and potentially disrupting the heteronormative values that imperial museums have historically upheld. A comparable – archetypal, even – narrative is seen in Derek Jarman’s 1986 film, Caravaggio, a freewheeling take on the baroque painter’s life through a postmodern queer lens.

There is something liberatory in this, and yet the stories are also stories of loss. Silveria Martin gives equal attention to photographs in gay magazines of the late 1970s and early 1980s, most often Blueboy and Olympus, titles referring to a notably camp portrait (c. 1770) by Thomas Gainsborough and the godly mountain of Ancient Greece that lent its name to a naked sports festival. The period lies on a generational cusp fraught with the tragedy of HIV/AIDS. And knowledge of this context adds poignancy to the stillness of the soft-pornographic images that Silveria Martin picks, instances of sexual promise, warm light falling like gossamer drapery over arched pelvises and toned torsos – holding the moment. This provokes desire, yes, but also our contemplation.

And so the pictures are a palimpsest – of loss, love and beauty. Poised stillness was an aspect of classical sculpture praised in the 18th century by the art critic and tastemaker Johann Joachim Winckelmann, whose descriptions of male nudes conspicuously betrayed a longing for ‘Greek love’ – a sentiment shared by the prototypical gay activist John Addington Symonds a hundred years later. Symonds was close friends with the painter Simeon Solomon, whose life was torn apart when he was prosecuted on two occasions for having passionate encounters with men. This exhibition is titled after Solomon’s richly allegorical, privately printed prose poem, ‘A Vision of Love Revealed in Sleep’, while Silveria Martin’s caringly rendered pencil portrait of him (2025) acts as the show’s commemorative talisman.

Hence Silveria Martin’s way of applying transparent paints to a base of loosely squeegeed diluted gesso, producing random shadowy traces and layered streaks, affords a sense of looking back and forth. Of the past rebounding in the present, disappearing and reappearing in non-linear, ruptured, furtive ways. The eye flits between looking at and looking through, like in a mirror or through a window and your focus shifts to a smear on the surface and what lies beyond it momentarily vanishes.